AI chatbot user interfaces — a seductive mirage

Part 2 of a three-part series of essays dismantling the illusion of AI chatbots: (1) the generative AI, (2) the user interface, and (3) the fictitious chatbot character

This is the third of four essays in a series dismantling the illusion of AI chatbots. The first essay introduced this series, and the second essay (part 1) provided a hands-on exploration of a generative AI system. This is part 2, an analysis of chatbot user interfaces. Part 3 explores the fictitious chatbot personas that power the conversational illusion. I ask in these essays: Who is on the other side of a conversation with an AI chatbot? What is this chatbot persona that is ready to happily write back at any time of day? How is this powerful illusion created, and why should we care?

The release of ChatGPT by OpenAI marked a pivotal moment in AI-driven appplications, popularizing a chatbot-like interface as the standard for human-AI interactions. ChatGPT’s rapid adoption demonstrated the appeal of natural language interaction, allowing users to communicate with AI through a simple, conversational UI.

User retention is a qualitative metric that assesses how well the interface engages users over time. High user retention indicates that the UI is effective, user-friendly, and encourages users to return.

These two quotations illustrate how computer scientists describe the role that the user interface (UI) plays in the experience of using a language model designed as a chatbot. What’s striking is that the familiar interface introduced by OpenAI in November 2022 has become the norm for consumer-facing AI-based applications. Through such an interface, developers transform a language model from a text-completion engine into something that feels like talking to a helpful friend or collaborator. This sense of a natural conversation is carefully engineered, appealing to our desires for interaction and harnessing psychological predilections to guide users’ experiences in visceral, emotional, and embodied ways. The end goal? User1 retention: keeping us hooked to the application so we continue using it.

AI chatbot user interfaces are a critical component in creating a persuasive illusion of an experience that feels like genuine dialogue with an equal interlocutor. In this series, I examine the importance of user interfaces as part of two other components:

The generative AI technology (language models themselves)

The specific user interfaces of AI chatbots

The fictitious chatbot character that completes the illusion of interacting with an intelligent entity

This essay addresses the second component. We want to take a closer look at AI chatbot user interfaces to understand better the role that UI design plays in how users interact with this technology. Such an understanding, I hope, will foster a deeper understanding that will help us determine whether to use an AI chatbot for a particular task and how to do so responsibly.

This essay provides explanations and numerous examples of what might be called a "critical interface analysis," drawing on Jennifer Sano-Franchini's work about Facebook's interface. This approach stresses that an application interface, as Sano-Franchini notes, "motivates, influences, and/or directs users' behaviors within and outside" a given technological artifact. The point is that user interfaces reflect a value system and an ethics of behavior for a technological artifact. The way technology looks and works isn’t neutral — it pushes users to act in specific ways and adopt certain attitudes and expectations. We want to analyze this process because it reflects a long cultural and popular obsession with talking machines2 and their realization through the current chatbot deployments by powerful corporations.

Every button placement, color choice, and navigation flow reflects the designers’ beliefs about how people should use AI chatbots and what actions and attitudes they should adopt.

The AI chatbot interface

To start, let's contrast two AI chatbot interfaces. The first one is the minimalist interface of NovelAI, the tool we examined in part 1 of this series. The second interface is Sudowrite’s, the self-proclaimed "Best AI Writing Partner for Fiction."

The contrast could not be more stark. NovelAI presents a minimal interface, a blank slate, into which a user is told in small, grey text to "Enter your prompt here..." If users want to add any other controls or options, they can enable navigation bars on the upper left and upper right (as indicated with red arrows). In this interface, users can enter any text they want, and a "Send" button at the bottom directs the GPT to generate additional text. Sudowrite, in contrast, presents a busy interface, dominated by three panels, many rounded-bubble clickable options, and a pastel-type color scheme. The page offers many additional options (many of them for automatic text generation of various kinds) through which a user scrolls vertically. The interface provides a range of clickable options that enhance the interaction quality of this program, suggesting that users should perceive all these different, fun options as a sign of trustworthiness and a commitment to helping them solve writing tasks as a writing partner, as its marketing tagline promises. The most prominently colored clickable bubble in this interface is placed in the lower-left corner — the "Upgrade" option, which collects subscription fees. I’ve always thought that Upgrade nudges play on people’s FOMO anxieties: they prey on our terror of being left behind, admonishing us that without these upgraded features, we’ll be cast into Luddite hell while the AI revolution thunders past us.

To create a chatbot interface that addresses the user as a consumer and conversation partner, two elements need to be added to a GPT system:

1. A chatbot input/output mechanism

2. Priming the user to provide input in the expected conversational mode

These two elements create the illusion that a genuine conversation between two interlocutors is taking place; in this way, the user participates in imbuing computational models with anthropomorphic functions. This mechanism is expertly delivered through a "graphical user interface" (GUI), which enables users to interact with graphical elements appearing on their display screens by pressing or clicking on pre-determined icons. GUIs are meant to be user-friendly and intuitive, unlike the older method of command-line interfaces, which required users to be more technically literate. AI chatbot interfaces feel intuitive, convenient, and accessible.

1. The chatbot input/output mechanism

Let's take a look at the automated chatbot mechanism first. The primary interface design for this element is a chat-centered user interface, which provides alternating message bubbles to create the impression that a "user" and a "bot" are participating in a conversation. We are familiar with such interfaces in many applications, for example, on our cell phones, where we interact with other people via chat windows in conversational messages, such as this one (from my own text messaging app):

We are also familiar with transactional customer-service interactions that occur in online conversational formats, such as this example from my recent interaction with Amazon’s chatbot:

Users encounter such conversational interfaces in commercial AI products, as illustrated in the examples below.

Here's Anthropic's Claude:

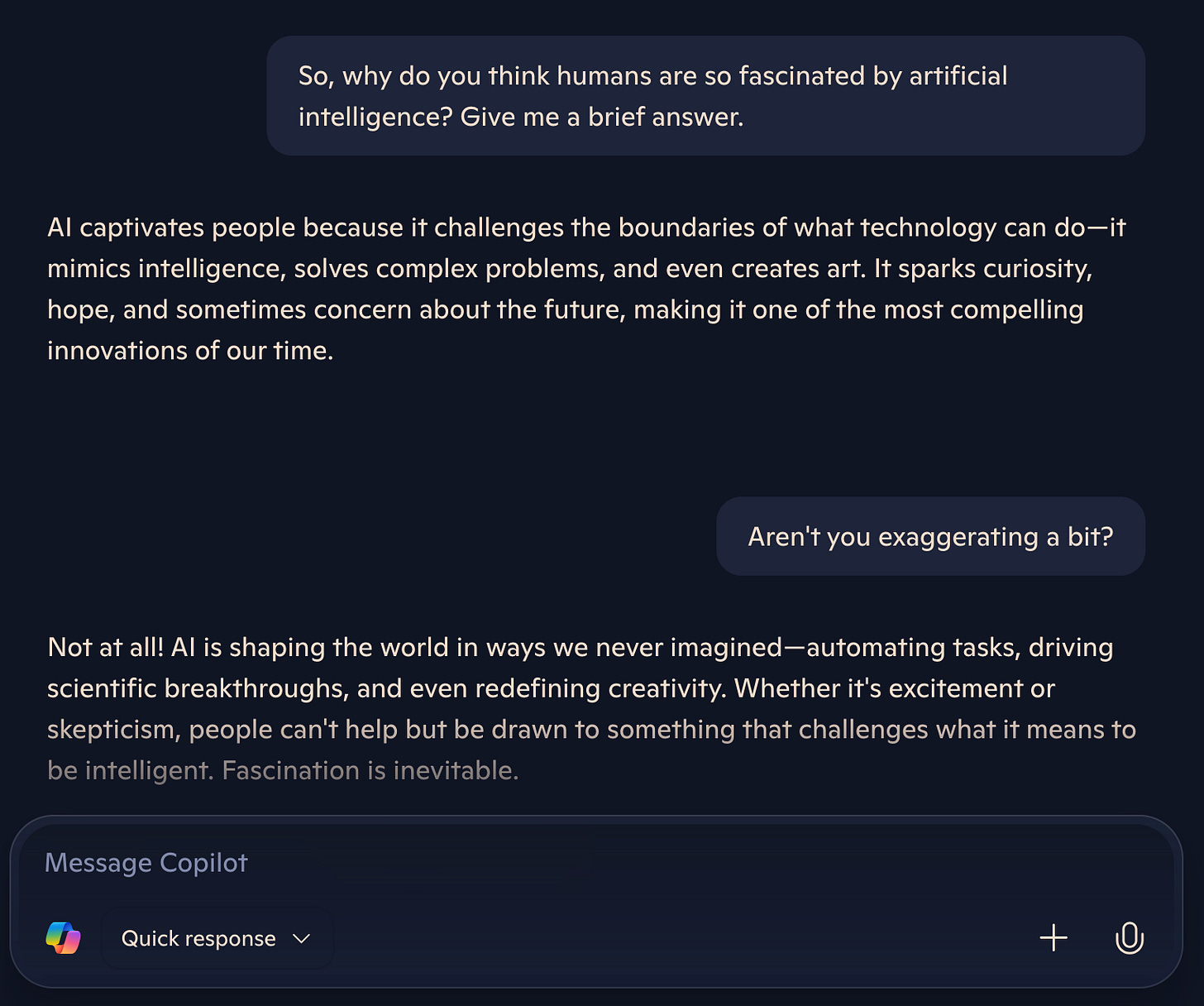

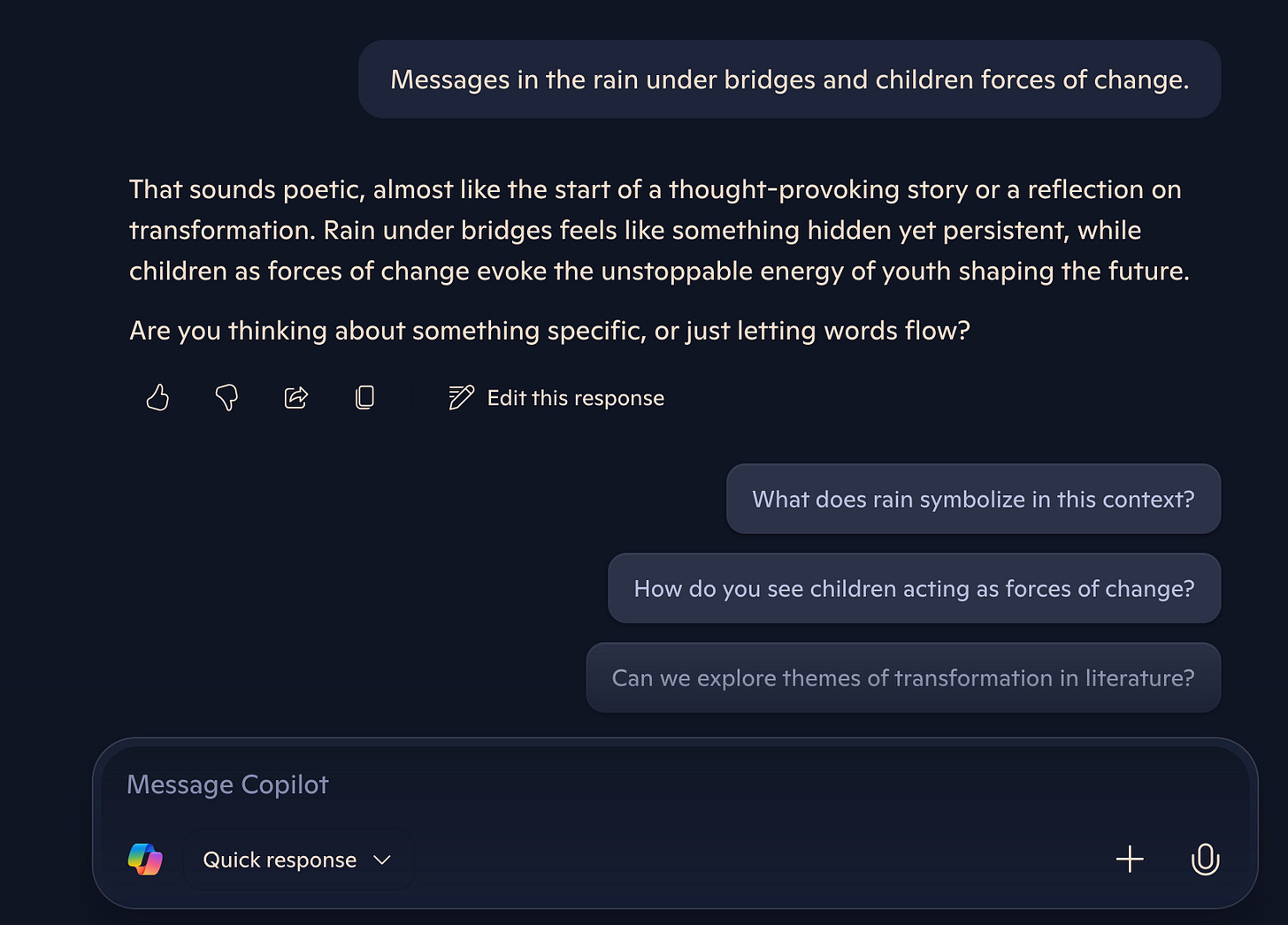

And Microsoft Copilot:

These conversation windows create a space that signals to the users that they’re entering a conversation mode, rather than browsing or searching. These bounded areas direct us to mentally shift into dialogue expectations, where we anticipate back-and-forth exchanges without any confusion. The clear distinction between the conversation area and input window helps users understand where to type and where responses will appear. The window format also limits the visual field and concentrates the user’s attention on this immediate conversation. It looks and behaves like any other chat we engage in on our devices, clearly demarcating the two speakers using different colors and fonts. But the font size is the same for both personas, thus signifying equal importance of both scripts and engendering trust in the output. Of course, it’s also essential to create such trust, especially when the AI chatbot delivers self-serving, hyperbolic, and confident claims about its purported transformational promise.

2. Priming users to adopt a conversational mode

For the conversational ruse to be complete, a user must be persuaded to talk to the language model in a conversational mode, addressing the model directly and using language that sounds like we’re talking to another person. As language models are fine-tuned to assign high probabilities to outputs that look like conversation transcripts, they will generate them more effectively as long as the user provides that style of text as input.

AI chatbot interfaces use a range of tactics and conversational framing tricks to make us adopt chat language, luring readers into the space of the bot’s enthusiastic and limitless subservience to our wishes and concerns. A few strategies and examples are included below (and note that more than one strategy is being used in each example):

a. Personalized message using the user’s name (Anthropic Claude):

b. Hyperbolic, optimistic promise of user agency in the prompt window (Perplexity):

c. Pre-designed suggested prompts, worded in imperative voice in separate speech windows (modeling how to address the imaginary interlocutor in second person singular) (Google Gemini):

d. Placement of the user as a customer in a transactional relationship with the bot (ChatGPT3):

e. A fully personified interlocutor (DeepSeek):

f. New prompts/questions and/or clickable icons to encourage users to stay on the page and continue the imaginary conversation (a few examples):

Overall, these chat interfaces push users to use social interaction patterns and consider the language model an interlocutor in a transactional relationship. The conversational flow design mimics natural interactions, bolstered by clear visual hierarchies, simple language (especially the use of the imperative voice), and straightforward navigation. Quick, personalized phrases convey an intimate and immediate feel, providing a cohesive overall experience. The bot addresses the user by name, offers its services, and presents a clear screen space in which the user can assume their role in the chat in relation to the bot. When the user engages in this conversational mode, the underlying GPT mechanism produces more predictable and satisfactory output. The potentially infinite token and word-vector possibilities are thus reduced to more manageable contexts that fit into typical conversational scenarios. In this way, users are also more likely to obtain output that they expect and find pleasing and suitable. In addition, chat sessions engage users through the social media strategy of infinite scrolling, thereby encouraging ongoing conversations and continued use of the AI chatbot.

But what happens when a user does not conform and does not play their role as a conversational partner? Let's try this strategy in Copilot by entering a text fragment that stylistically does not resemble a typical conversation:

The bot maintains its role as a conversationalist, suggesting a coherent-sounding reply to my nonsensical text, and ending with a conversational question intended to convince me to return to a chat-style register. In addition, below this chat, the model also adds, in separate conversation-style icons, specific questions that return the thread into chat mode. Finally, the text box at the very bottom commands me to get back into the chat by "messaging" Copilot (formulated, again, in second-person singular imperative voice).

The majority of prompt engineering tips and guidelines focus on crafting effective prompts that elicit the best responses from AI chatbot products. Such prompt templates are tailored to play this conversational game as well as possible. For example, the formula or recipe for a good prompt below creates an ideal conversational scenario, including personas, imperative voice action verbs in the second-person singular, and specific instructions that a personalized bot is supposed to follow.

The curated and tightly controlled conversation mode of commercial GenAI interfaces creates a powerful illusion that two conversation partners interact with each other. These interfaces direct users to stay within those bounds and cooperate in maintaining roleplay and sustaining a consumer-based, satisfying, and frictionless user experience.

The concept of frictionless user experiences deserves a tad bit more attention. In their orientation towards a user-friendly and easy operation, AI chatbots seamlessly join a long tradition of easy-to-use technological artifacts for the mass consumer market. In fact, to a large degree, after World War II, an ideology of ease has dominated the consumer economy, emphasizing ease as a logic and principle in its own right. Under this value, consumer satisfaction is presented as the embodiment of what technical communication scholar Bradley Dilger has called, in a 2006 book chapter, "extreme usability:" the doxa that, in the development of technological systems, the goal is to create extremely user-friendly, convenient, and expedient designs that facilitate quick adoption.

In the process, however, Dilger cautions that extreme usability design can actually diminish user agency. While especially novice users are invited to easily adopt new technological artifacts, they are not privy to the underlying mechanisms. They are essentially excluded from having any real understanding of and control over the technology and its deployment. What matters is the feeling of consumption as an expedient, frictionless experience, facilitated by pleasant user interfaces and user experiences. It is worth quoting Dilger's full argument here:

Extreme usability also extends the ideological framework of ease as well, bringing the assumption of a commercial context, lack of critical engagement, and desire for speed and convenience typical of consumer culture to our understanding of technology. Like ease, extreme usability encourages out-of-pocket rejection of difficulty and complexity, displaced agency and control to external experts, and represses critique and critical use of technology in the name of productivity and efficiency (p. 52).

The implications of the design of current AI chatbots are inescapable. As we have seen on this page, these programs and tools employ user interfaces that call on us as consumers in interactions that are easy, fun, fast, and convenient. The chatbot format lends itself exceptionally well to such interactions that seem nearly hypnotic in their smooth, interactive dynamics. A form of learned helplessness can develop as users are unable and unwilling to engage with technology that requires a learning curve. Only the experts know how these systems work, and we are trained to trust them implicitly. The pursuit of extreme usability becomes a form of social control. Of course, the public is primed for such consumer-based conversations after years of engaging with each other through social media and other digital communication technologies.4 We are more than willing to normalize AI chatbots as if they were real conversation partners.

If we consider, however, how large language models work, these conversational interfaces obscure the fact that these bots function on a transformer architecture that computes linguistic probabilities to predict a likely next word. The user interfaces for commercial AI models present products that are framed as being able to execute the factual and real tasks we throw at them. Especially the incessant injunctions to use the imperative voice and instruct the AI chatbot to complete a specific query or task, reveal a category error in how users are asked to perceive and use language models. These user interfaces imply that models have some baseline ability to report facts accurately (and only occasionally malfunction). This framing fundamentally misrepresents how these systems actually work.

AI chatbots do not have a special factual mode versus a creative mode in their computational process, despite the explicit invitation to treat them as equal conversation partners that can execute our commands. These models are still probability distributions and pattern matchers before user interfaces anthropomorphize the process.

But, for the chatbot interface to fully convince users of the illusion of a real conversation, one more "ingredient" must be optimized: the bot must have a personality to be made to become one's collaborator, assistant, or writing partner. The next essay in this series deals with this final element.

Notes:

The term “user” itself already carries implications about the relationships between people and technology. Users are consumers that take from the technology; users are objects in the market; users consume something others have created; users follow prescribed pathways; users are not developers, designers, creators; users don’t have the technical knowledge concentrated among the experts; users are drug addicts in their compulsive consumption of technical tools.

Lucy Suchman calls this obsession “an imaginary of the computational sensorium.” She explains,

Framed through the trope of communication, moreover, these foundations were posited as the model not only for signal processing but also for human cognition and social relations. In the ensuing decades the intelligent, interactive machine has become an established figure in discussions of information technology, from scientific and professional discourse to popular media representations (p. 70).

ChatGPT (like most other commercial products) offers a rotating selection of conversational framing phrases to address users and steer them into chat mode: “What’s on the agenda today?” “Ready when you are.” “Good to see you, [user name].” “What are you working on?” “What’s on your mind today?” “Hey, [user name]. Ready to dive in?”

Another important precursor to normalizing chatbots as part of daily communications (in the workplace and private environments) was the popularization and accessibility of email applications. In 2006, Myra G. Moss and Steven B. Katz described the deliberate introduction of email into consumer-based web applications as a move to align this new technology with the existing values of efficiency, time management, and convenience. In the following passage, one can easily see how AI deployment fits into this process:

Email is not primarily about or only about “reaching out and touching someone.” That is not why companies produce email products, whether corporate or personal. It is about providing a service to make profit. Perhaps more important, the effect of this capitalistic ideology is to fundamentally alter, through the valued embedded in the communication medium of email, the relations of users to machines, to each other, and to themselves, turning the purpose of that relationship into the work of technological capitalism (p. 84).